I may have easily sleepwalked the first twenty years of my life away with incuriousness and the next twenty years with busyness, if it weren't for the wake-up calls of a silent God Who repeats Himself. I remember silk webs and sprouting seeds and the warm breath from my horse's nostrils; I remember the first days home with each new baby—long, quiet hours that were permission for rest and awe; even every sickness, a reminder. All these things have woken me again and again. Still, it's easy to skim over and rush through and ignore the repeated messages—to fall asleep again.

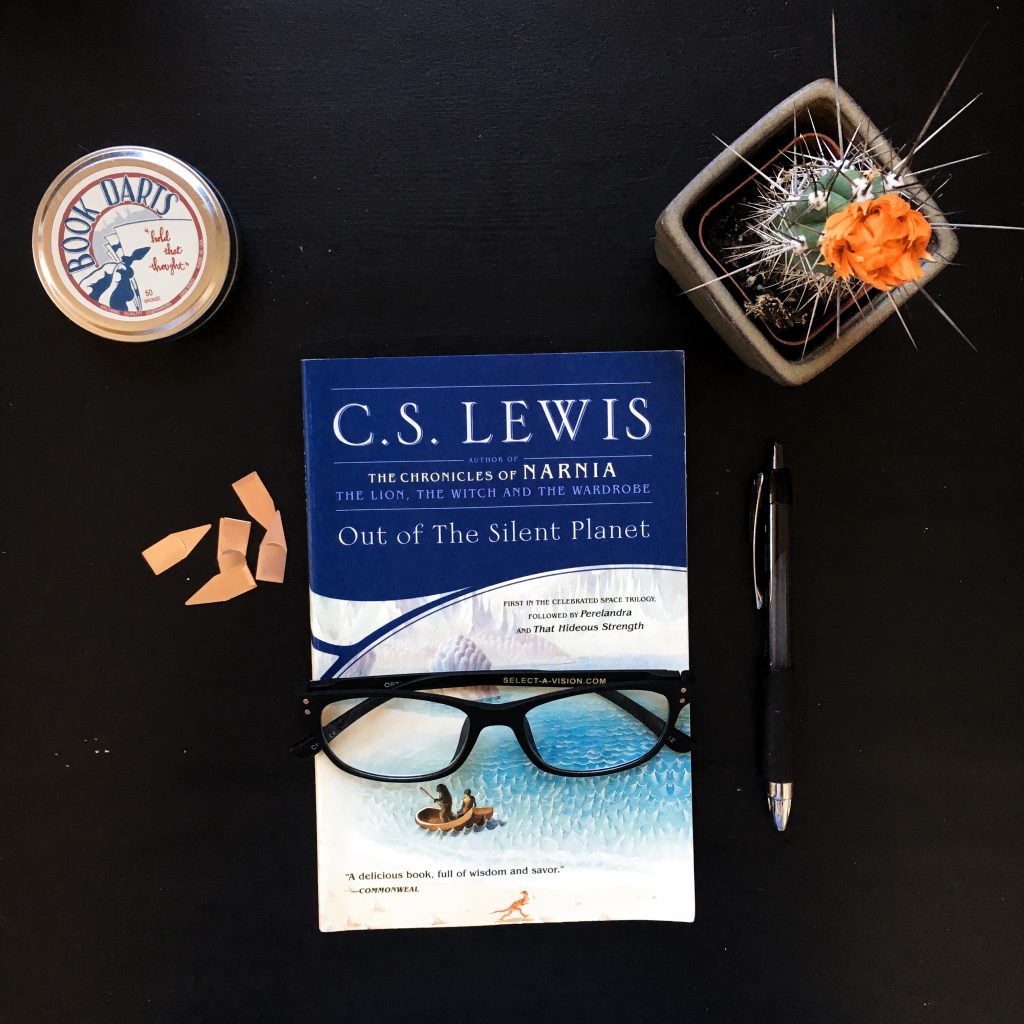

One morning last week I plowed through to the end of Out of the Silent Planet. I say 'plowed through' because I was at the point of just wanting to finish the book for the sake of finishing (there are two more books in the series to get to!), not necessarily because I had to force myself to get through the book. I am slow about most things, and part of my reading-slowness comes from the fact that I have an overwhelming list of books in queue — I'm great at starting but terrible at finishing and I get distracted by shiny things.

So I finished the book and turned randomly to Chesterton's In Defense of Sanity, a collection of his essays that are perfect for finishing.

None of this is consequential in any way, except that at the end of Silent Planet and ten minutes later in Chesterton's essay "The Drift from Domesticity", was the same multi-syllabic word I'd never seen before (or at least, never noticed).

These were both paper copies, so it wasn't possible to highlight the word and look up its definition like I could if it were on my Kindle. I didn't exactly know the word's meaning—I gathered brief clues from the context the first time I read it; but when it came up a second time, ten minutes later and in a different book altogether, I paid more attention.

I do that: I skim over things in an effort to progress, or rather, to make progress, which is different. Filling quotas and stacking books is only progress if you are taking an inventory or managing a library. I tend to file ideas for later and seldom get back to them, creating a backlog of Things I Should Know and Books I Should Read, and I carry that log around in mental space that could be better used.

Or, I keep 750 tabs open on my computer and my "save" section on Facebook overflows and my Goodreads list is unreasonable for a person of my attention span.

If an unknown word pops up twice in two different places in the first hour of my day, however, I will pay attention, look the word up, notice its latin roots and derivatives, and get way too excited about the coincidence of it all.

I will be a nerd about these things, and I will be disappointed if you're not as excited as I am about it (looking at you, my Latin 2 students).

Somnambulist: n. a person who walks in their sleep.

Chesterton's essay was all about our propensity to miss the value of things we don't understand, to dismiss traditions or boundaries or institutions because we don't see their use and don't take the time to understand why they are in place. Using an imaginary fence or gate across a road as an illustration, he compares two reformers: one who sees the fence as useless and immediately wants to clear it away, and another who will not think of tearing it down until he understands the point of it.

It was not set up by somnambulists who built it in their sleep. It is highly improbable that it was put there by escaped lunatics who were for some reason loose in the street. Some person had some reason for thinking it would be a good thing for somebody. And until we know what the reason was, we really cannot judge whether the reason was reasonable. It is extremely probable that we have overlooked some whole aspect of the question, if something set up by human beings like ourselves seems to be entirely meaningless and mysterious. There are reformers who get over this by assuming that all their fathers were fools; but if that be so, we can only say that folly appears to be a hereditary disease.

Skimming the facts, passing quick judgements, and focusing on making progress are not really admirable qualities. They are not the kinds of things I would hope for, for my kids or my husband or myself. After all these years of homeschooling and living and waking up together, one of my greatest hopes is that we would all be more curious.

Sometimes it takes repetition—the same word twice in one morning, the same message in two different books, the same scripture, same look, same symptom—before we can really wake up to a fact. Being fully awake would gives us eyes to see the interrelatedness of all the things, working together.

It's safe to assume something is being repeated in your life, because you are worth communicating with and the tendency to sleepwalk is as inherent as our foolishness.

Pay attention to that thing you hear a second, third, and fourth time.